6 Questions to Tackle in Using Assessment in Instruction

12/23/2017

The amount of hours we currently assess our students is under fire…and rightly so! The plethora of assessments ranging from state, district, and even school testing requires our students to show what they know more than ever. Accountability is the name of the game. Some states test over 30 hours per year on standardized assessments. A new statute requires schools to test less than 2% of the allotted instructional hours as delineated by the state. That does not take into account district and school assessments, which might add on another 20-30 hours per student. For example, in Montana, they require 1,080 instructional hours a year. Some school districts assess around 40 hours per year. Calculate how many hours your students are assessed.

As we see increased accountability in all aspects of society, especially in government spending, schools have not been immune. Communities want to know that their tax dollars are being spent appropriately in our schools. What test scores do not highlight is the amount of growth our students make, as well as the strong culture of learning in a school. That being said, many in educational research are blasting the amount of time students spend testing. No one in education is arguing that all testing should be abolished, but if we are going to test, let's make sure the data is being used to drive instruction…not policy!

Assessments come in two forms, summative and formative. Summative assessment data tells us what students have learned over time, or "assessment of learning." Formative assessment data, on the other hand, tells us how students are doing along the journey of learning, or "assessment for learning." The data tells two different stories of a student. Formative data is used daily to drive instruction for the class and for individual students. The data gives educators the teaching points of emphasis for the next steps in the instructional path. A student could score low on all the formative assessment checks, and then ace the summative test at the end. Vice-versa, a student could bomb the final assessment, but score proficient on all the formative checks along the way. In both cases, the teacher must be reflective on how the classroom data and adjust curriculum, instruction, and assessment. This dynamic balance is hard to define, even for veteran teachers, and many struggle with the formative data driving their instruction.

This is one of the most difficult components of Charlotte Danielson's Evaluation Model in order to score the illusive, "Exemplary." Here are six questions that can take you from teacher-driven assessments to student-driven success!

1 - How Do I Develop Strong Assessments?

Assessments are created from specific learning criteria. Criteria at each grade level is devised and approved by each state agency. Many states have chosen the Common Core State Standards in which they have built each grade level's criteria. Questions are then devised according to those criteria, which are touted to be the learning goals for creating students that are college and career ready. Most states are associated with one of two assessment companies: Smarter Balanced Assessment Consortium (SBAC or recently simplified to "Smarter") and Partnership for Assessment of Readiness for College and Careers (PARCC). Both tests are specifically built from the Common Core Standards. The SBAC is a computer adaptive test that gets easier or harder after a student answers a question correctly or incorrectly. The PARCC is a computerized assessment made similar to the Smarter Assessment. This test is not computer adaptive.

States can chose to pay for additional interim assessments that can be given at the beginning and middle of the year which can help determine what students need to know in order to pass the year-end assessment. In this fashion, these assessments can be used to determine individual, classroom, and grade level instructional goals for the remainder of the year.

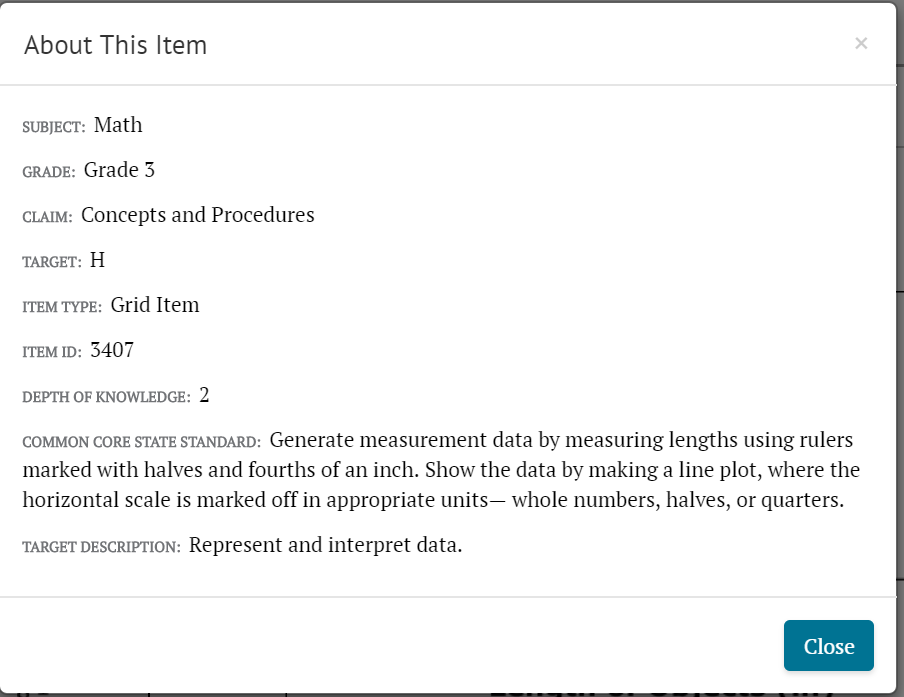

Here is an example of a Common Core State Standard and a corresponding Smarter Assessment Question (taken from the Smarter Balanced Items):

At the school district level, school boards approve a curriculum that best covers the state-adopted learning standards at each grade level. While some states have devised their own standards and have not adopted the Common Core State Standards, all school districts must adhere to their states approved learning criteria. While many curriculum and textbook companies advertise that their curriculum meets all the states standards, school districts must be cautious and supplement standards that are not adequately addressed in the content. For example, in Montana 15% of the state required standards are based on Indian Education for All curriculum. The state requires school districts to implement curriculum that best meets those learning targets. The state has many resources for school districts to use, but the implementation and accountability of meeting the requirements is placed back on individual school districts.

At the school level, teachers are required for the most part, to follow the school district's approved curriculum. Many exemplary level teachers may find resources that best meet the learning targets and the students seated in their classroom. Communication between a school's administration and classroom teachers are vital when veering away from the district-mandated curriculum. Districts can create assessments that check for student mastery according to the curriculum. In addition, districts and schools can create formative assessments that are used to inform teachers throughout the learning, and before the final assessment.

When questions are devised for online participants, the types of questions are limited to specific response formats. Both Smarter and PARCC assessments use similar question formats (According to Smarter and PARCC web sites):

- Selected-response items prompt students to select one or more responses for a set of options.

- Non-traditional response questionstake advantage of computer-based administration to assess a deeper understanding of content and skills than would otherwise be possible with traditional item types. These kinds of questions might include drag-and-drop, editing text, or drawing an object.

- Constructed-response questionsprompt students to produce a text or numerical response in order to collect evidence about their knowledge or understanding of a given assessment target.

- Performance tasks measure a student's ability to demonstrate critical-thinking and problem-solving skills. Performance tasks challenge students to apply their knowledge and skills to respond to complex real-world problems. They can be best described as collections of questions and activities that are coherently connected to a single theme or scenario. These activities are meant to measure capacities such as depth of understanding, writing and research skills, and complex analysis, which cannot be adequately assessed with traditional assessment questions. The performance tasks are taken on a computer (but are not computer adaptive) and will take one to two class periods to complete.

Anyone creating a test has to determine what level or depth of knowledge each question is for the test taker. Using Bloom's Taxonomy is one way to delineate the test items at various learning levels. Students will be responding to questions through an online format, which may limit students to some degree. Both the Smarter and PARCC assessments advertise that test questions give teachers powerful information to inform instruction and improve teaching. Both assessment companies have a review process to determine whether a question is effective at giving educators the needed data to inform instruction. Likewise, curriculum or textbook companies require students to respond in several formats and the questions can be from a variety of levels according to Bloom's Taxonomy. With an emphasis on rigor and relevance, higher levels of questions are more evident on these assessments than ever before.

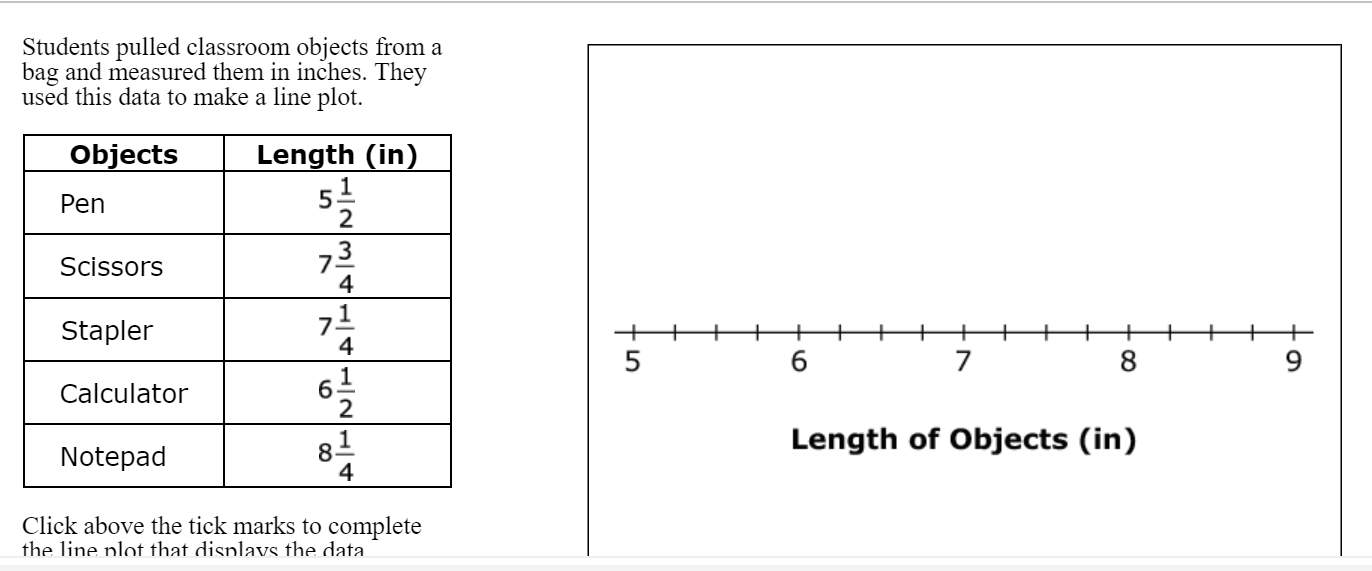

Alternative assessments can be more powerful than aforementioned assessments. Alternative assessments take into account a student's strengths. If a student can use one of their strengths to determine mastery of content in another area, why would we not take advantage of these alternative options! In addition, what a computer cannot do is determine a student's strengths. For example, a student could chose to be assessed from a menu of performance tasks that correspond to Howard Gardner's Multiple Intelligences. This student is artistic and has strengths in the "visual and spatial" intelligence. He chooses to create a comic strip that describes the Revolutionary War, "Shot heard around the world." Here is a menu of assessment tasks that fit almost any learning criteria (From the Sweet Life of Third Grade Blog)

2 - When I Monitor Instruction and Pose Questions, How Does This Information Help Me Create Strong Formative Assessments?

In the past decade, there has been a push for stronger data and information to drive instruction before a final test. In traditional classrooms, a summative assessment at the end of the unit told educators how students mastered the content. In many cases, this was too late to change instruction, and teachers did not have a lot of time to go back and reteach the unit's content. In progressive and proactive classrooms over the past decade, teachers are devising formative data that drives instruction on a daily basis. In this fashion, teachers believe they can assure that all students are mastering the content along the way. Powerful and effective formative assessment data helps predict how students will do on the summative assessments at the end of the unit.

Many school districts have created common formative assessments for teachers to use with the district-mandated curriculum. In other school districts, teachers create their own formative assessments to use with students. Whatever is chosen for use, the data should drive the next steps for instruction. Assessments that are given and the data is not being used are a waste of time and these practices should be reviewed.

Formative assessments should be devised from the learning criteria for a given lesson, or unit of study. Starting with the end in mind, working backwards is a best practice. This practice is well defined in McTighe and Wiggins, Understanding by Design. After summative assessments are created, aligning formative assessments will give educators powerful information for making instruction decisions.

Formative assessments should be quick for students to take, as well as informative for teachers to determine student needs and instructional effectiveness. Here are 20 quick formative assessments according to blogger Sarah Dougherty:

- Outcome Sentences

- Conga Lin

- Inner/Outer Circle

- Headlines

- Plus, Minus, Interesting (PMI)

- Pair-Share

- Paired-Squared

- Jigsaw

- Modified Jigsaw

- Affirmations

- 3-2-1

- Quick Write/Draw

- Gallery Walk

- Think-Write-Share

- Red Card/Green Card

- Beach Ball

- Exit Tickets

- SOS

- Poll the Class

- Self-Assessment

3 - When I Review the Formative Assessment Data, What Are My next Steps?

Many teachers agree that formative assessment needs to be used in classrooms. Yet, some of these teachers do not know what to do with the data that is collected. Exemplary teachers have plan; they understand that something needs to be done with this data immediately. A teacher needs to alter instruction and curriculum for individual students, small groups, and even for classrooms according to the collected data. Personalizing the learning, or differentiation, is proven to be a powerful instructional practice and intervention.

For example, after giving the students a formative assessment titled, Exit Ticket, a teacher learns that 65% of her class understands the concepts that have been taught that day. A teacher must determine the next steps. Unfortunately, some teachers move on. Exemplary teachers dig deeper into this formative data. They answer the following questions when they look at the data:

- What individual students mastered the lessons content?

- What individual students partially mastered the lessons content?

- What individual students need extensive support in mastering the lessons content?

- Can I create groups from this data that will make instruction more efficient?

After these questions have been answered and students have been grouped, then a teacher must decide on what the best instructional strategies should be used for each individual students or for groups of students. Gone are the days of teaching it "louder" and "redoing the same instructional strategy" when re-teaching a concept. Exemplary teachers must change the curriculum materials or instructional strategy to meet the needs of the individual students or groups of students. Differentiating the process, content, or product, as described by Carol Ann Tomlinson, is best practice. Read more about Tomlinson's research here.

4 - How Does Effective Feedback Play a Role in Assessment, by the Teacher and Peers?

According to research by John Hattie, student feedback is one of the top ten influences on educational achievement (according to Feedback in Schools). Too many times teachers hand back an assessment without ever giving any verbal feedback, or merely writing a grade on it. The grade of course symbolizes the effort level of the student that parents and society have been accustomed to for over a century. Yet, there is more behind this grade. Exemplary teachers understand that behind a letter grade of "C" there is a whole other story about student achievement. Feedback on student progress should start in the beginning of the lesson. It should continue during the lesson as students are forming their understanding of the concept, as well as at the end of the lesson…when typically summative assessments are given.

In the article, Feedback in Schools, Hattie discusses seven understandings that teachers should follow when giving effective feedback (as summarized by the author of this blog):

- Feedback should focus on specific learner progress towards a standard or criteria. The more specific and individualized, the most effective.

- The culture of the classroom and the teacher-student respect level is vital to how effective the feedback is received, and the amount of change that can occur.

- The greater the disconfirmation, the greater the possible change.

- Creating an environment where errors are acceptable, and adhere to the philosophy, "errors are where the new learning goes," lead to higher performance.

- The use of peer feedback can be powerful is used appropriately.

- Assessment feedback gives both student performance data, as well as teacher effectiveness data.

- The use of specific feedback strategies can enhance learning.

John Hattie further discusses that feedback strategies should follow these criteria:

- Focus feedback on the task, not the learner,

- Provide elaborated feedback,

- Present elaborated feedback in manageable units,

- Be specific and clear with feedback messages,

- Keep feedback minimal, but not simpler,

- Reduce uncertainty between performance and goals,

- Give unbiased, objective feedback, written or via computer,

- Promote a learning goal orientation via feedback,

- Provide feedback after learners have attempted a solution

5 - How Can I Teach Students to Monitor Their Own Work Creating a Stronger Sense of Agency?

Transferring power to students in order to monitoring their own learning can be difficult. There are many strategies teachers can use in order for students to create a strong sense of agency. Teachers can use are self-assessment and self-reflection, they provide for closure at the end of every learning segment, and they can use rubrics, checklists, and peer assessments. These are all strong metacognitive practices that can start as early as kindergarten and can be found in effective teacher's classrooms all the way through a student's schooling.

Self-assessment can be included in all lessons at the beginning, middle, and even the end of an instructional segment. Students can first score themselves against criteria in a pre-assessment. Finding out what they know about a subject area, schemata (as coined by Jean Piaget), can be a powerful tool for teachers. Teachers can then determine how deep and how fast they can instruct according to pre-assessment data from students. This data can tell a teacher areas of strengths and areas of needs for individual students, as well as holistic data for the class or grade level. Combining this pre-assessment data along with prior summative data give the teacher various data points in order to make more effective and efficient instructional decisions.

Self-assessment conducted in the middle of the lesson segment gives teachers data to inform instruction. The data lets teachers know if students are on the path to achieving the overarching learning targets. In addition, the data lets the teacher know how effective their instruction is so far and gives them direction on pacing and mastery of content. The power of self-assessment data along with teacher formative assessment data give the teacher two data points in order to make more effective and efficient instructional decisions.

Self-assessment at the end of the lesson provides students a chance to self-reflect on where they started from in the lesson or unit segment, and where they are at the end. Using summative assessments coupled with formative and self-assessment data inform instruction for exemplary teachers. These teachers understand that data drives instruction and they have evidence to inform the decisions they make.

Checklists, rubrics, and peer assessments are devised to organize and chunk learning; they can be strong tools for creating agency. When a student follows a checklist in order to complete given tasks, they are in charge of their learning. Likewise, when rubrics are used, students can set a goal with the given criteria. If the rubric is clearly communicated, delineated out so students can ascertain the given criteria, increased student achievement is evident. Peer assessments can change student products and increase student achievement. When a positive learning culture is created in a classroom, peers play a vital role in assessing their peers. When the information is used in a formative nature, students can improve their work. Peers can work on collaboration skills, teaching others, as well as creating a strong positive learning environment when done appropriately with respect and kindness.

6 - How Can I Differentiate the Assessments for the Students?

When a teacher uses assessment data to drive instruction, differentiation is a powerful strategy to meet individual, group, and classroom needs. Differentiation seeks to determine what students already know, what they need to learn, as well as allowing them to demonstrate what they know through multiple methods. Lastly, it encourages students and teachers to add depth and complexity to the learning process.

Recently there has been a few articles in the news about the difficulties of effectively differentiating instruction. The arguments by James Delish in a 2015 Education Week article, Differentiation Doesn't Work, state the following two reasons why this strategy is failing in our schools:

- Too wide of abilities in a classroom to effectively teach what each student needs.

- Confusing with teachers on what to differentiate, the curriculum or the instruction, or both?

To some degree, Delish's arguments are viable. Exemplary teachers in Charlotte Danielson's Model understand that differentiation is the key to individualizing student learning. In the past decade, personalized learning has become a prominent goal for educators across the country. Addressing students needs is a difficult task. In Carol Ann Tomlinson's article on the Reading Rockets web site titled, What is Differentiated Instruction?, she defines differentiation. Since 2000, this definition is still considered best practice in education today,

"Differentiation means tailoring instruction to meet individual needs. Whether teachers differentiate content, process, products, or the learning environment, the use of ongoing assessment and flexible grouping makes this a successful approach to instruction."

Exemplary teachers have started with small adjustments in these four areas. They experiment with how to differentiate the content, process, products, and learning environment effectively. As they get more experience with differentiating, these teachers have made larger adjustments. A couple of examples, a teacher may start with differentiating the content in a Daily 5 reading structure. All students are reading books at their appropriate level. A math teacher may need to fill holes with one group of students adding double-digit whole numbers, while the majority of students are working on multiplication facts to nine, and a top group is working on double-digit multiplication. Instructional strategies and student products are going to look different for specific students; everyone is getting what they need. The more experience a teacher gets with differentiating; the easier it is to meet student's needs. Having a multitude of instructional strategies, as well as materials, supports differentiation ideas. Starting small is the key.

The ability to differentiate the products or assessments for students can be individualized with formative and summative data, as well as self-assessment data. The use of Howard Gardner's Multiple Intelligences and Bloom's Taxonomy, as stated above, can also give teachers ideas on how to differentiate assessments. There needs to be a mix of assessments for students; not all assessments can be differentiated. Though we would like assessments to all be at their readiness levels, we must also use normative or grade level assessments to determine progress, too. Students will still need to take state testing, ACT/SAT, etc. in order to get into college, as well as determining their progress towards mastery of grade level norms. A teacher's pathway to differentiate effectively starts on the first day they set foot in the classroom.

(Charlotte Danielson Model: Domain 2 Component d)

MORE ROCK MY EVALUATION RELATED READINGS:

- Being Exemplary When Communicating with Students

- Using Questioning and Discussion Techniques

- Engaging Students in Learning

- Using Assessment in Instruction (Currently here)

- Demonstrating Flexibility and Responsiveness in the Classroom

- Learning How to Say No and Set Boundaries with Parents - November 21, 2022

- If You Had Only One Behavior Strategy to Use in Your Classroom, What Would It Be? - September 26, 2022

- Live Your Code: 7 Strategies That Will Help You Be the Most Effective Educator You Can Be - August 15, 2022