4 Strategies to Reframe Student and Parent Comments to the Positive

3/12/2019

Have you ever wanted to change the words that someone says? As an educator, reframing words is a conversational skill that can be very tricky, but very effective in the success of a student. Many times we using reframing to change negative self-talk or unhealthy perceptions of others. The best educators can do this without much conflict.

I am lucky enough to be part of a school that believes in the power of parent/teacher conferences. For the first time in my tenure we had 100% of parents participate in our fall conferences either face-to-face or phone call conferences. This past week, we had spring conferences where 92% attended in person.

We set our expectations high for parent contact. We use a three tries policy in my school. I ask teachers to try to set up a face-to-face conference. They try three times if unsuccessful the first two. If they can't get a parent in they then try a phone call. If they still can't contact parents, then the teacher gives me their names and I send a letter home talking about their progress and the need to team with us for the benefit of their child. This letter goes into the child's permanent file showing we have tried three times for a conference. Fortunately, I have not had to send out very many letters with this procedure in place.

As a principal, I team with teachers for difficult conferences, as well as coming in to celebrate students. Teachers can ask for the counselor, literacy specialist, resource teacher, and Title I teacher to conferences as well. This teaming helps support the classroom teacher, but it also is one more person when the parent meeting might be difficult.

When we have difficult parent meetings, we are constantly looking to frame things to the positive. We talk about academic growth over the academic scores, and growth in social aspects. When we do this, there are times we have to reframe conversations in order to stay positive. If we dive into the negative with the parent, we set ourselves up for failure, as well as the student.

There are many strategies we can use to reframe conversations. You may ask, "what about telling parents the truth about their child?" In no way am I saying to not have these conversations, but after we discuss growth areas or specific needs of the student, we must provide hope that teaming with parents, we can support their child. We base this on the premise that all children can learn.

1 - Cultivating a Growth Mindset

If you have been education for any time period, by now you have heard of Carol Dweck's work with growth mindset. In the past couple years I have seen tons of meme's on Facebook and Twitter that show how we can reframe our thinking and our words. In fact, many teachers create posters and even anchor charts in their classrooms. They specifically teach their students on how they can describe their feelings with a growth mindset. As educators, we hear students that are hard on themselves and their self-talk is destructively negative.

Likewise, when we talk with parents of students that have a strong negative self-talk, we find where much of this language may be permeating. So many parents care about their child with 100% effort, yet may not know that some of their verbiage can be destructive in nature. These are difficult conversations to have with parents. No one wants to hear from another adult that what they are saying to their child is hurtful. Yet, I believe part of our job as educators is to provide hope and team with parents. Having a growth mindset will set the student up for success, and during our conversations with parents we may reframe some of the thinking and processing. Here is a great meme that gives an example of how we can reframe these conversations with both students and parents.

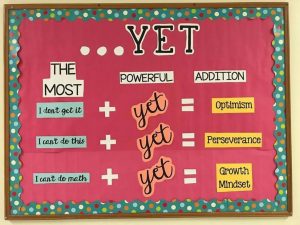

2 - The Power Of "Yet"

Too many times you hear students say, "I can't do it." We need to automatically add the word "yet" to this phrase. This added verbiage changes the meaning of the phrase and provides hope. Hope that if we don't understand it right now, we will in the future. Finding tools, strategies, and actually practicing are three ways we can go to solution when we make the comment, "I can't do it, yet."

Not only does "yet" provide a sense hope, but also the concept of grit. We know that grit is the number one determining factor of success according to Angela Duckworth's research. "Yet" means we are not giving up and we will find a solution to our problem. Using "yet" we understand that it may take perseverance over a long period of time.

When we have conversations with parents we sometimes hear them say, "I was horrible at math and I can't do it. I am sure my son can't do it either." Here is where the concept of "yet" takes shape. We can talk with parents about what we can do at school to support their son. In addition, we can give them ideas to support them at home so they can team with us. We can provide the idea of hope and the fact that we believe we can support their student in school.

3 - "You Get To"

When working with students we often hear them use the phrase, "I don't want to go to school," or "I don't want to talk to my teacher." Helping students understand that so much of what we do have in the United States sets us apart from other countries. We are lucky to have a free and appropriate public education, which many other countries do not. We can reframe this thinking by telling students, "You get to go to school today," or "You get to talk with your teacher today." Changing the verbiage changes the meaning of these phrases.

Empathy and compassion tend to be the backbone of these conversations when we use the phrase, "you get to." Putting students in someone else's shoes and showing kindness to others helps them reframe their own perspectives. Since it is free, taking education for granted is something we may have done at one time. We need to reiterate that education opens doors.

Similarly, talking with parents in meetings educators hear phrases such as "I don't want to go to a parent teacher conference," "I don't want to help my child with math, he should be able to do it on his own," or "I don't want to go to the holiday concert." As an educator, these conversations might be a bit trickier to reframe with parents. I believe if a parent is not going to be the primary advocate for their child, then we must be and support them. You have to be careful to not overstep your boundaries, but helping reframe the aforementioned phrases into the following: "You get to come listen to me celebrate your child's progress," "You get to support your child at home as you are more of the primary teacher than me. In addition, I can give you information and material to help you support your child at home," and lastly, "You get to go to your child's holiday concert. Before you know it, they are out of school and you will no longer be able to attend."

Using the phrase "I don't want to" or "I have to" implies it is an encumbrance because we have to do something. When we use the phrase, "You get to," it implies we have an opportunity. When we make this switch from "I don't want to" into the phrase "You get to," it changes your perspective on life. Many people don't get the chance to do these things with their child or student. Understand that we are only with these people for a short period of time in the overall span of our lives. In addition, thinking about the many students that attend our schools who have been through trauma or even a loss of a parent is stifling. The phrase "you get to" becomes even more powerful in our lives.

4 - "What can we control (and what we can't)"

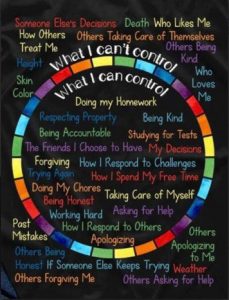

What students think they can control at times is can actually be uncontrollable. Many times they do not understand how to communicate and process a situation. We know students need structure and the ability to predict what's going to happen with their world around them. They are attracted to these environments that provide this nurturing structure. Unfortunately, the ability to control all variables in any environment is impossible.

Teaching specifically what students can and cannot control can be taught by educators using graphics or visuals to show them there is a sphere of control. What is inside the circle are things we can change and control. Those outside the circle we cannot control. We can then teach how to determine if the variable is either in our circle or outside. If it is in our circle, we can give strategies to help control the variable. If it is outside of our circle, then we must let it go…and likewise, there are strategies we can use to support us letting it go.

Similarly, working with parents we sometimes have to talk about the things they can control at home, what we can control at school, as well as the factors that neither of us can control. In our school, we build ownership of our behaviors as well as building independence.

In our school, the goal is for students to leave sixth grade heading as independent learners that take ownership of their behavior, actions, and words. Like parents, we can model language and model actions, and we can even practice this before students implement it. Ultimately, the sphere of control in these situations lies with students.

For example, if they believe a friend is upset with them, we as educators and parents can ask questions, model questions and responses, and practice conversations before the student tries to fix the situation. We practice this because if we get involved in the early stages of these critical conversations, we relinquish the power of the student, as well as enabling the student to have an adult solve all their problems. We want students to always start the conversations first with their words.

In my school, we may even model this language with the other student right there, "Jimmy, you may tell him to stop poking you." Having students be the first to problem solve their situations helps them develop into independent thinkers. It also helps them determine what they can and cannot control much faster without our support.

- Learning How to Say No and Set Boundaries with Parents - November 21, 2022

- If You Had Only One Behavior Strategy to Use in Your Classroom, What Would It Be? - September 26, 2022

- Live Your Code: 7 Strategies That Will Help You Be the Most Effective Educator You Can Be - August 15, 2022